My 2xgreat grandmother was born and grew up in Luton, in Bedfordshire, joining many thousands of others working in the booming straw hat industry, probably from a young age. She would have earned good money, which may be why she didn’t immediately marry the father of her first child. What would Hattie’s formative years in the hatters’ heyday have been like?

Straw hats and plaits: Luton’s boom

In the 1871 census, Harriet Scrivener was living at 23 Stuart Street in Luton’s town centre. Her father William was a groom, while Harriet, her mother Hannah, sisters Mary Ann and Sarah, were all described as hat sewers. Harriet was the middle sister, aged 20; Mary Ann (whose name is transcribed as Margarite on the census form) was 34 and Sarah, 15. The name Harriet is often shortened to Hattie; I don’t know if that was the case with Harriet Scrivener, but it would certainly be an apt name for a hat sewer.

Image generated by AI

Many sources, including The Luton Hat Industry website, suggest that straw plaiting, and the subsequent sewing of braided plaits into straw hats, had started in and around Bedfordshire by the early 1600s, with Luton at its centre. By the mid-1800s, a straw plait market had been set up in George Street, very close to Stuart Street. Many hats were sewn and shaped at home rather than in large factories, with some houses being extended to accommodate the family’s work. Selvedge.org describes the plaiting process used in the straw hat industry:

“Straw plaiters worked with a bundle of straws or splints under the left arm, each straw being moistened between the lips before being worked into the plait — this gave many plaiters a characteristic permanent scar at the corner of the mouth. … In order to turn straw plait into a hat, the plait must be sewn in a continuous coil, starting at the crown and ending at the brim. … Most of this hand sewing was done in the home or in small establishments before being sold onto larger firms.”

Image generated by AI

The Scrivener women’s early experiences of straw plaiting and bonnet sewing would have likely seen them working at home. But

“in the late 1870s sewing machines were introduced and used for sewing hats which in turn led to big factories being established in the town centre; many of these factories also supported the associated cottage industries of plaiting and hat-making”.

Perhaps, by 1871, Harriet and her sisters were already seeing changes and heading to factories to work. One such was situated in Bute Street, where Harriet’s future husband and father of their 13 children, Jesse Ephgrave, was lodging in 1871.

Childhood and family

In the 19th century, the straw hat industry brought growth to what had previously been a small market town. In 1801, Luton’s population was just over 3,000. By 1871, when Harriet became pregnant with her illegitimate son Frederick Hipgrave Scrivener, it had exceeded 17,000. Harriet grew up in a town that had had gas light since 1834. In 1850, the year before she was born, a Board of Health was formed and set about building sewers. A water company was formed in 1865 and by 1870 the whole town had a piped water supply, bringing much-needed fresh water into homes. However, many would still have relied on shared water pumps in the street and smelly paraffin lamps or candles to light their homes, and work by.

Harriet Scrivener makes her first appearance in the census records aged just two months in 1851. She is enumerated as the youngest child of William Scrivener, 38, a groom originally from Limbury in Bedfordshire, and his wife Hannah, 37, from Luton. Hannah is working as a bonnet sewer as is eldest daughter Mary Ann, aged 14. They have another daughter, Louisa, who is just two years old. Also in the household is Sarah Hawkes, a 77 year old widow, who was Hannah Scrivener’s mother (which makes her my 4xgreat grandmother) born in Potton, Bedfordshire as Sarah Stokes in 1774.

Harriet’s birth certificate shows that she was born on 13 Janury 1851 at Elizabeth Street in Luton. At the time, her father is working as a labourer, an occupation he alternated with groom on various records over time. Her mother registered the birth, making her mark as she could not read and write. It’s something of a miracle, then, that the Scrivener surname was spelt fairly consistently in other records.

Extract from birth certificate for Harriet Scrivener (GRO)

Old maps of Elizabeth Street do not reveal any distinguishing features or buildings and today’s view from Google maps is of a mix of red brick terraced cottages and modern flats. It is a short street close to Wellington Street, one of Luton’s main shopping streets from mid-Victorian times. In the 1851 census, the family’s immediate neighbours in Elizabeth Street included a gardener, an engine worker and a carpenter. Amongst the females, all over the age of 12 are bonnet sewers, apart from one needlewoman.

The Hat Industry of Luton and its Buildings (PDF) published by English Heritage in 2013 notes that children as young as four were taught in ‘plaiting schools’ how to split and plait straw and, once proficient when older, sew hats and bonnets. Unfortunately I have not been able to find any of the Scrivener family in the 1861 census, when Harriet would have been ten years old. Harriet signed her name on her marriage certificate in 1873, so would have had some schooling, although I haven’t found any records to say where, and there are few others records for the family that indicate what her childhood might have been like.

However, the 1851 and 1871 censuses show quite a gap between Harriet’s older and younger sisters Mary Ann (b 1836) and Louisa (b 1848). Further research shows that their parents had had at least four other children before Harriet: their second child, Frederick, was born just before Christmas in 1837 and died, aged nine months, in September 1838 from ‘teething’. Siblings Jane, Henry and Edwin died aged four months, three months and four weeks, respectively. Their cause of death is recorded as ‘decline’ or ‘debility’. Essentially, the babies weren’t strong enough to survive, perhaps couldn’t keep food (milk) down, and wasted away. However, the term was also used to cover an underlying cause such as pulmonary tuberculosis.

The first three children’s death certificates just give place of death as ‘Luton’; Edwin’s shows that he died at Elizabeth Street in October 1846, so the family had been there at least five years by the time Harriet was born. Elizabeth Street was a recently-developed area of new housing in Luton in the 1840s. While, to 21st century eyes, ‘new housing’ might suggest decent standards and conditions compared to housing in previous centuries, a teaching pack put together by Luton Museums Education Service (PDF: L StrawHat Boom.qxd) paints a somewhat different picture:

“To meet the growing demand for housing, Luton first expanded into present day New Town, High Town and Park Town. With no kind of planning authority or building regulation a lot of cheap housing was built quickly from poor quality materials. Many homes had tiny rooms with dangerous stairways and no lighting, heating, water supply or sanitation. The 1850 Board of Health Report descriptions of the town and its neighbourhoods are almost unimaginably squalid”.

Luton: Straw Hat Boom Town 1890 to 1910. Luton Museums Education Service.

It may have been in such conditions that Harriet’s family lived, and some of their children died.

A baptist family?

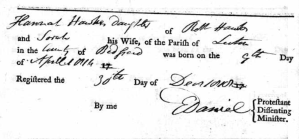

Harriet’s parents married in the Anglican parish church of St Mary, Luton, by banns, in February 1836. I couldn’t find any baptism records for Harriet or her siblings, which was puzzling. It seems that, despite her place of marriage, Harriet’s mother had been brought up a baptist from at least the age of four; her parents recorded her birth in Luton’s baptist church on 30 December 1818, together with those of their other five children, the eldest born in 1800.

There are further clues to Hannah’s baptist faith. Sarah Hawkes, Harriet’s maternal grandmother, was living with the family at Elizabeth Street at the time of the 1851 census. Two months later, she died there, aged 77. The cause of death was ‘natural decay’, ie old age. Her daughter Hannah registered the death, making her mark. She was buried at Luton’s baptist meeting house on 27 May 1851 (FindMyPast). There are burial records in FamilySearch’s non-conformist record collections for unnamed Scriveners, with dates which match the deaths of Frederick, Jane, Henry and Edwin; this and the absence of child baptism records for the children suggests that the family were all baptists.

World War I memories of Luton website notes that baptism had been a growing faith in Luton since the 1700s. Ebenezer Daniel had been the baptist minister in Luton since 1812, and it is his signature that appears on the Hawkes children’s birth registrations in 1818.

Extract from baptist birth register Luton (Ancestry)

At that time, the baptist meeting house was at the house of a George Evans. By the time that Harriet’s grandmother died, the baptist meeting house may have been in Castle Street (established 1837) or the Luton Union Baptist Chapel in Caddington (1846).

Main Sources:

- Baptism and burial records (Ancestry, FindMyPast, FamilySearch)

- Birth, marriage and death certificates (GRO)

- 1851-1871 censuses (Ancestry, FindMyPast, The Genealogist)

- Luton Memories website

- National Library of Scotland maps

- English Heritage

- Luton WW1 Memories website